VIdéoH / HIVideo : (other) Cultural Responses

The essays in this dossier are expanded versions of talks given by Conal McStravick and Vincent Bonin at a panel discussion and a screening at the Cinémathèque Québécoise on 1 August 2022. McStravick responded to Journal of the Plague Year (After Daniel Defoe) (1984) by British artist and theorist Stuart Marshall (1949-1993) and Bonin to Le récit d'A (1990) by Quebec filmmaker Esther Valiquette (1962-1994). To accompany The 24th International AIDS Conference Vidéographe has put online a special video program of works from the collection selected for Vithèque by co-curators Vincent Bonin & Conal McStravick. You can find it here : https://vitheque.com/en/programmations/videoh-hivideo

VIdéoH / HIVideo (Other) cultural responses culturelles : VHI/AIDS and video in Montreal (1984-1990)

The essays in this dossier are expanded versions of talks given by Conal McStravick and Vincent Bonin at a panel discussion and a screening at the Cinémathèque Québécoise on 1 August 2022. McStravick responded to Journal of the Plague Year (After Daniel Defoe) (1984) by British artist and theorist Stuart Marshall (1949-1993) and Bonin to Le récit d'A (1990) by Quebec filmmaker Esther Valiquette (1962-1994). The discussion amongst the speakers and with the audience was moderated by scholar Maria Nengeh Mensah from the Université du Québec.

Unfortunately, we cannot go into the full richness of the exchange that took place here. We would like to take this opportunity to thank Nengeh Mensah for her exceptional contribution to this project. We wish to thank Karine Boulanger, former curator of the Videographe collection, who invited us, and Sarah Boucher, who acted as interim curator during the course of finalizing the event’s organization, and the preparation of the dossier.

McStravick has researched and written about Marshall's practice for several plus years. The work he addresses here, Journal of the Plague Year, brings back-to-back two moments, one contemporary in 1984 and the other historical. Through video vignettes, the viewer hovers between the rise of homophobia in tabloid newspapers at the start of the HIV/AIDS crisis in London in the early 1980s, and the emergence of sexology as a discipline at the turn of the 20th century in Germany, which was halted by homosexual persecution during the Third Reich. McStravick chose to focus on this installation for the panel and dossier because its inaugural presentation happened in the framework of Vidéo 84, a significant international video art event held in Montreal. He situates this work within Marshall's corpus and emphasizes the artist's Canadian trajectory, from Montreal to Vancouver, via Toronto. He also highlights how Marshall helped shape a critical discourse on HIV/AIDS whose complexity still resonates with us today.

Bonin was commissioned by Videographe to write an essay on Esther Valiquette’s Le récit d’A. This experimental documentary stemmed from the video maker editing various filmic and photographic images taken during a sojourn to California with an audio recording of the words of Andrew Small, a gay man from San Francisco who was outspokenly HIV positive. The polysemy of the two intricated testimonies has, later on, provided the opportunity for curators and critics to situate Valiquette’s video within many instantiations of the video program genre most often bound by the limits of the thematic cluster. Bonin offers an analysis of the reception of the work by focusing on the history of early HIV/AIDS exhibitions in Montreal since the early 1990s in which it was shown. He also uses the extensive chronology of Le récit d’A’s screenings between 1994 (the year of Valiquette’s passing) and 2022 to address the concept of posthumous authorship, and the contemporary circulation of statements made in the 1990s by persons with AIDS (pwas).

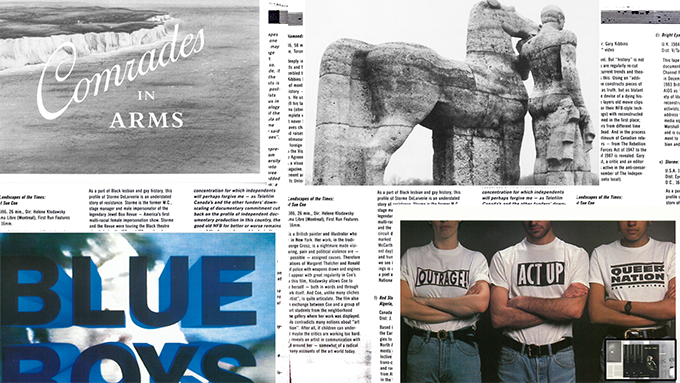

Although Marshal and Valiquette seemed to have little in common at first, apart from living with HIV/AIDS, we noticed some overlaps between their practices. For example, the dates of the inaugural showings of the works, separated by 6 years, place them in a narrative timeline – which remains to be written – of art and activism against HIV/AIDS in Montreal. The 1980s were a particularly dark time of abandonment for pwas. In 1984, when Journal of the Plague Year was conceived, activism was still scarce. Marshall's installation could therefore be described as the inaugural themed HIV/AIDS work presented at a major contemporary art event in Montreal. Le récit d’A is one of the first “coming out,” as Thomas Waugh has stated, made by a positive woman in Quebec using the medium of video. As they complement each other, our texts have also bridged two decades of the crisis which were separated by the epistemic break of the fifth AIDS conference in 1989 held in Montreal. This gathering of mostly medical professionals behind closed doors became a rallying point for activists in North America. It gave rise to an uprising led by ACT-UP (New York), AIDS ACTION NOW (Toronto) and RÉACTION SIDA (Montreal) denouncing lingering political apathy and asking for patients to play a new reformatory role in research protocols. The conference program also had a cultural component, SIDART, organized by Ken Morrison, which, among other “responses,” included a selection of video works. The activism of the early 1990s in the aftermath of the 89 conference, enabled artists like Valiquette and Marshall to gain visibility, and, in addition, chapters of ACT-UP, like the Montreal group, to find traction. Morrison and Allan Klusaček’s post-SIDART 1992 anthology of essays A Leap in the Dark offers another view of this period in Montreal. The book, which was recently reedited, refers to Marshall but occludes Valiquette, who indirectly responded to but was not present within SIDART, yet whose own trajectory overlaps with Marshall’s and whose work resonated for many during the subsequent three decades. Le récit d’A as well as Valiquette’s whole corpus, has often been entrenched in the poetic, in contrast to Marshall's analytical method and the prosaic form of other video practices emerging from the United States, United Kingdom and English Canada during the same period.

The convergence and divergence of positions within a discourse around HIV/AIDS are also reflected in the history of the collections of the distributors of these works. These are LUX, in London, and Vidéographe, in Montreal. Their catalogues each include a very different constellation of examples of HIV/AIDS video activism stemming from distinct cultural contexts, francophone and anglophone, which nevertheless resonate with the experiences and struggles shared by many positive people. When these localized speech acts are brought together, as was the case during the panel and now in this dossier, they draw the outlines of a wider archive.

The title of the panel and dossier, VIdéoH / HIVideo : (other) cultural responses. HIV/AIDS and video in Montreal (1984-1990), offered a situation where one might encounter Marshall’s Journal of the Plague Year, first exhibited in 1984, and Valiquette’s Le récit d’A, first screened in 1990, together for the first time. It explored these ‘debuts,’ and the timelines of these AIDS-related works through many contexts, not least, our own critical and queer cultural present. While an unforeseen capacity for a shared analysis is acknowledged here, Marshall and Valiquette’s works must nevertheless be considered as both historically and critically distinct objects. However, one other discursive site that made this comparative method possible was captured in the utterance ‘(Other) cultural responses,’ itself a placeholder title for ‘other cultural responses,’ the title of the programming of AIDS activist video, performance and ‘other’ more intermedia-type iterations within Ken Morrison’s SIDART (where one of Marshall’s works, Bright Eyes (1984), was screened). At the end of the eighties, this placeholding act had already found a new nomenclature in what Douglas Crimp and his allies defined as ‘AIDS cultural activism’ during the forgoing period.

In 1983, Marshall traveled to the US and Canada to research an activist documentary for the UK’s Channel 4 on the homophobic and pathologizing representation of AIDS as the ‘gay plague.’ Through this trajectory, whose outcome became the work Bright Eyes, he first encountered the neo-gay lib AIDS activist ideas of Michael Lynch in Toronto and the safe sex evangelism of Michael Callen, Richard Berkowitz and Joseph Sonnabend in New York. One segment of Bright Eyes is an adaptation, in a drama-documentary “reenactment” style, of the news story of a San Francisco gay man who was denied an audio mic to speak on live TV as pwas. In 1989, recovering from an AIDS-related illness, Esther Valiquette sought out communitarian voices in San Francisco to understand her own experience as a positive woman. After interviewing many gay positive men, she singled out Andrew Small a legal secretary, who shared with his friend Paul Castro, the man portrayed in Bright Eyes, a similar experience of being ostracized on his job, in court. The jurors refused to be in the same room, with him. In the meantime, Small had become a media-ready AIDS activist in San Francisco. His ‘story’ then formed the basis for Le récit d’A.

Vincent Bonin and Conal McStravick

You can find here a video program on works around HIV/AIDS in the collection of Vidéographe, which was assembled by Conal McStravick and Vincent Bonin : https://vitheque.com/en/programmations/videoh-hivideo

Re-viewing Le récit d’A

Vincent Bonin

When did I first encounter Esther Valiquette’s corpus? I was still too young to have attended screenings of Le singe bleu (1992). In the 2000s, this film and her videotapes were not widely shown. It is very possible that my recollection of Valiquette as an artist, and a person living with AIDS, was formed without having seen her works, by way of a text by Jean-Claude Marineau, published in Parachute.[1] Much later, I was able to watch Le récit d’A when Vidéographe’s collection was made available online through its catalogue, Vithèque.

There, on the videotape’s page, we can read a short artist statement (taken from an interview published in Le Devoir in 1991[2], and an extract from an essay by critic Nicole Gingras. At the very bottom of the page, below these fragments of text, appear the keywords ‘essay’, ‘narrative’, ‘AIDS’, ‘desert’, ‘poetry’ and ‘youth’. A quick search using the term ‘AIDS’ brought up an eclectic list of works from the collection – including Le récit d’A – around the common denominator of the disease. Even without the addition of a commentary, a ghostlike historical constellation was sketched from the retrieved data. The dates, parenthetically gathering these tapes, indicate when they had been produced during the crisis, pre- or post-1996, the pivotal year in which approved antiviral treatments became accessible in certain parts of the world.

Valiquette passed away in 1994 and didn’t leave any archives. Even Vidéographe’s fonds contains few documents that can help to provide contextual information on the genesis of Le récit d’A. Her project proposal, which she would likely have submitted before receiving approval to make the work, is missing. I, therefore, had to rely on published sources (essays and newspaper articles) and the testimonies of a few individuals who were close to her, to write this text. I found a rare interview in 1992 between Valiquette and Claudio Zanchettin, in which she describes the circumstances of her coming to filmmaking and video:

“I am a 30-year-old woman. I worked as a film technician until four years ago in 1989. I did a Bachelor’s degree in visual arts and went on to do internships at the NFB, where I ended up working as a camera assistant. I was trained at the NFB and in the private sector and my goal was to make images: I wanted to be a director of photography. I therefore worked as lighting assistant to learn the technical side. We all have our purgatory before leading a team! I took a career break because the illness appeared very severely. I was working at this time on a film by Tahani Rached, Le chic resto pop. I stopped and asked myself some serious questions about what I was going to do. I belonged to a very open and supportive working environment. My friends organized a fundraising campaign and, thanks to the insurance provided by the union for film technicians, I had a salary for one year. I had a certain amount of flexibility and when my health began to improve a little, I went to California, to San Francisco. I brought a Super 8 camera with me and a tape recorder. I wanted to go on a pilgrimage by myself in the desert but, first of all, I wanted to meet people who had survived AIDS. I was told (it was the period of “Congrès de 89”) that certain […].”[3]

The interview is inexplicably interrupted at this point, when Valiquette mentions the 5th International AIDS Conference in Montréal in 1989, which has become a changeover event in the timeline of the struggles against the disease. The inaugural gathering – attended by medical doctors and politicians – was stormed by HIV-positive individuals. Members of New York’s ACT UP, Toronto’s AIDS ACTION NOW and Montréal’s RÉACTION SIDA then published a manifesto demanding, among other things, that patients be involved in the trials of new treatments.[4]

We will never know the real impact that the conference had on Valiquette’s trajectory. Researcher Chantal Nadeau, who was very close to the video maker, described the first iteration of the project Le récit d’A in these words:

“Valiquette wanted to make an ethnological study by interviewing gay men in California who were still alive after being diagnosed HIV-positive several years previously. She carried out more than 30 interviews […]”.[5]

However, in the final edit, Valiquette retained only the testimony of Andrew Small, a legal secretary who worked at numerous gay and lesbian rights community organizations in San Francisco. An article in the Washington Post in 1988 mentions him in a description of the gay neighbourhood, Castro, which has been transformed significantly since the crisis began.[6] Small also appeared in the televised report Struggling with AIDS made by journalist Randy Shilts for the San Francisco channel KQED in December 1989.[7] He recounts a traumatic episode of homophobic stigmatization that many gay men could have experienced during this period: in June 1983, during a trial, the jury members refused to be close to him.

In Le récit d’A, Valiquette created a relation of transference so that Small’s words could be spoken without him having to describe, once again, the circumstances of the violence he suffered.

There are several videos by HIV-negative filmmakers in the 1980s that give voice to people who were HIV-positive. One example is the video Danny (1987) by Stashu Kybartas, whose question-and-answer structure recalls the interview format of Le récit d’A. It is worth noting that, during this period, the hate speech of homophobia, exacerbated by the epidemic, was often triggered by the sight of blemishes on the skin of persons living with AIDS (caused by the Kaposi’s sarcoma, a type of skin cancer). Kybartas showed photographs of Danny, whose face was marked with these stigmata, while the subject’s testimony could be heard as voice-over. Valiquette uses an analogue method of creating discrepancies between the soundtrack and the image, but, unlike Kybartas, she retains only voices and conceals both Small’s face and her own. Was this aniconic approach the result of technical constraints (she had only a tape recorder and Super 8 camera at her disposal) or was it a deliberate choice, despite the fact that Small’s body had been represented in the media?

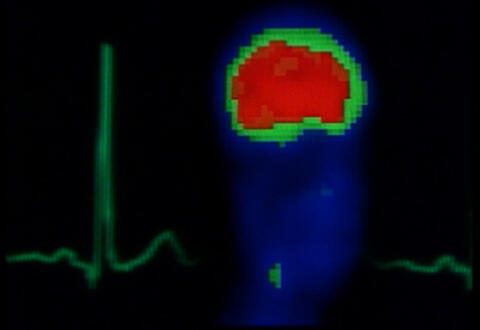

Le récit d’A was intended, above all, for an HIV-positive audience. When the interview took place, Small had already lived with HIV and AIDS for seven years. He describes a period during which the profile of the illness hadn’t yet been entirely defined. However, in comparison to authors and artists whose work could correspond to the genre of autopathography (Audre Lorde, Jo Spence, Hannah Wilke), Valiquette inverted the clinical gaze, but refrained from turning the camera towards her own body or Small’s. She manipulated the impersonal visual traces embedded in her medical file by, for example, superimposing the charts of a tomography examination (MRI) of her brain over the raster frame of the videographic screen. The soundtrack that accompanies these images is made of noises like the rolling clicks and blips of the scanner.

These procedural documents, in principle legible only to specialists, are nevertheless filled with affect for those who must encounter such an abstract representation of themselves. Nadeau postulates that the recurring medical imagery (Valiquette’s second work, Le singe bleu (1992), comprises microscopic modelling of the virus, and infographic tableaux showing the collapse of T4 cells), stand in for the HIV-positive body. Yet, despite this dissociation between her subjects’ voices and visual representation, this body is not completely relinquished. In Le récit d’A, the image of a naked man appears intermittently, within a white space that resembles a chroma key studio. The anonymity of this model (the critic and painter Marcel Saint-Pierre) led to misrecognition over time, as some people believed it to be Small. However, there is nothing to corroborate this fact in the video or elsewhere. This abandoned being becomes the substrate over which the brain scans, sub-titles and, ultimately, fragments of text from Edmond Jabès’ The Book of Margins (Le livre des marges, published in French in 1987) are superimposed. Scrolling from the bottom to the top of the screen, and sometimes read aloud, these quotations from Jabès’s work evoke, among other things, the concept of blankness (“blancheur” in French), which alternately denotes an unmarked surface, the act of tabula rasa, a beginning, and an end. The Jewish Egyptian author placed himself between the injunction not to speak for the witness and his duty to transgress this limitation. The unmarked page and the desert have become, for him, figurations of a void that language cannot fill. In expanding this aporetic logic through the instability of the video signal, Valiquette alternates Jabès’ texts with images of Death Valley in California, ‘the youngest desert on the planet’ (her words), to give a form to the illness’s ontological loss.

In 1992, Valiquette decided to put aside the complex dialogical structure used in Le récit d’A. She also moved away from the LGBTQ struggles that Andrew Small’s voice enacted. In her second work, Le singe bleu, made in 1992 for the National Film Board, Valiquette shows her empty hospital room – again concealing her body – and images, filmed during a trip to Greece, of Minoan ruins. The civilization on the island of Santorini had been annihilated by a volcanic eruption 1600 BC. In her off-camera voiceover, going back and forth between ‘tu’ and ‘je’ (‘you’ and ‘I’), she likens the AIDS pandemic inexorably decimating populations to the accidental human destruction following a natural disaster. The figure of the blue monkey (‘le singe bleu’), encountered on one of the Minoan frescos, represents the ‘other’, the HIV-positive individual. In 1993, Valiquette made her final work Extenderis (produced by Vidéographe), interrupting the performance of her testimony and foregrounding the scientific images that appeared sporadically in Le récit d’A and Le singe bleu. In a choral structure reminiscent of an apocalyptic psalm, she juxtaposes fragments of archival black and white footage of 20th century political events and natural disasters with computer graphics reminiscent of the spiral shape of DNA code. For her, this language heralded the afterlives of a biological trace, beyond anthropomorphism and after the finitude of the body. Yet, at a pivotal moment, Valiquette situates herself as a subject amongst these abstractions. Her face appears behind a microscope, her eye scrutinizing a sample of blood, attempting to step back and observe this virus, indifferent to her. Despite what distinguishes them, the three works address a fundamental ambivalence towards the regimes of visibility that define the person with AIDS.

It could be said that the recursive and retroactive narrative forms in Le récit d’A – the way it goes back and forth between different temporalities of living with an illness – foreshadowed the conditions of the works’ posthumous reception. Very often Small recalls the circumstances in which he had to find the right words to describe his own, unexpected, symptoms. When Valiquette met her interlocutors in San Francisco in an attempt to understand how they survived, she herself was close to facing the irreversible bifurcation of the virus. When she asks Small how he is still alive, he doesn’t answer, not knowing, and says instead that over the course of the past seven years, his whole life unfolded before him. The video concludes with a glimmer of hope, but it doesn’t prevent the fact that finitude lies on the horizon and, ultimately, the work would be seen without the artist’s words to accompany it.

Expanding on Roland Barthes’ theory of the death of the author in the era of AIDS, Ross Chambers postulates that certain HIV-positive filmmakers and writers envisioned from the outset the mode of address of their texts so that discourse about the work could exist in their absence.[8] Laura U. Marks compares the tactile materiality of video to the vulnerability of disappeared bodies that are represented there.[9] What we remember from the reception of Le récit d’A, however, seems to foreground the inaugural event (even the ‘patient zero’), the beginning rather than the end. In this framework, the work would be sought to articulate a rare declaration of HIV-positivity by a woman, through the medium of video, in 1990. Precedents include the film Liars and Women: Activists Say No To Cosmo (1988) by American filmmaker Jean Carlomusto (HIV-negative), denouncing the false assertion by psychiatrist Robert E. Gould that women were generally unlikely to contract HIV.[10] In Quebec, a year before the first screening of Le récit d’A, Le sida au féminin (1989) by Lise Bonenfant and Marie Fortin (both HIV-negative), gave a voice to women living with HIV/AIDS, though not without ceding to a certain level of sensationalism.

Valiquette’s speech act, in which she declares her HIV-positivity (a ‘coming out’ according to Thomas Waugh), would also have had the effect of breaking a silence lasting several years in the Montréal art field (see the end of this text for more on this matter).[11] Paradoxically, the rupture alluded to by Waugh remained a blind spot in the initial analyses of the crisis as an ‘epidemic of representation’ that took place in English Canada after the 1989 conference. I will now look at the video’s reception between 1990 and 1992, both in and outside of the parameters of the almost monolingual theoretical discourse about HIV/AIDS in this field.

In 1990, Le récit d’A was screened at Cinéma Parallèle, along with other videos distributed by Vidéographe, and was then presented at the gay and lesbian festival Image & Nation. In 1991, the video received the audience award at Silence elles tournent. The same year, it was screened on the periphery of the interdisciplinary event Revoir le sida organized by Allan Klusaček and René Lavoie at the Maison de la Culture Frontenac. Klusaček and Lavoie had brought together works from the British exhibition Ecstatic Antibodies and a selection of Québécois productions.[12] They were members of Diffusion gaie et lesbienne du Québec, the organisation putting together the Image & Nation festival since 1987.

The 5th AIDS conference in 1989 was accompanied by a partly didactic ‘cultural programme’ entitled SIDART, curated by Ken Morrison. In 1992, Klusaček and Morrison collaborated on the anthology A Leap in the Dark, a book in English only, compiled of essays by Canadian, American, and British authors.[13] Valiquette’s work isn’t mentioned in the book, although videos by John Greyson, Gregg Bordowitz and many others are built into the exegesis. In an interview with Daniel Carrière published in Le Devoir in 1992, Valiquette highlights that it was difficult to screen Le récit d’A without the message of prevention, one of the criteria used to determine if videos about HIV/AIDS could be politically effective.[14] On the other hand, she said, “community groups that find that there aren’t enough of this type of document, became interested in the work.”[15]

Thomas Waugh attempted to explain the problem of the poor reception of Le récit d’A outside of francophone Quebec. According to him, one of the reasons that the work had not been included in critical discourses on HIV/AIDS (for example that of Morrison and Klusaček), was the absence of English subtitles:

“Valiquette’s beautiful work had the disadvantage of being in French and English at once and almost inaccessible in either language versions, as well as feeling a bit literary for anglo tastes and both dated in its political innocence and ahead of its time in its confrontation with the metaphysics and iconographies of corporeal mutability.”[16]

It could be said, however, that the work in its original form, too ‘opaque’ and already almost saturated with words, constantly underlines translatability and cultural transfer (between French and English, Montréal and San Francisco). Waugh’s commentary also leaned on a lingering perception that artistic practices in Quebec during the 1990s were restrained by the overconsciousness of language and the poetic register (Valiquette’s ‘literary tastes’), whereas at that time their anglophone counterparts were taking action with a sense of political urgency.[17] For Waugh, the video was therefore arriving late in the course of the history being written and, at the same time, referred to the future of a plasticity of the body, though he didn’t linger on this part. In wanting to rehabilitate the work, he places it at an impasse of communicability, a quasi-state of aphasia. Vidéographe recently added subtitles to Le récit d’A, and the screening at the VIdéoH / HIVideo : (other) cultural responses. HIV/AIDS and video in Montreal (1984-1990) event constituted its first official bilingual screening.

In order to situate this phenomenon of travelling statements, but this time in reverse (the migration of an activist proposition, parachuted to Quebec from New York), I will go on a tangent and briefly consider the failure of the dissemination of Gran Fury’s posters in Montréal in 1992. The project, entitled Je me souviens, was commissioned by the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal under the banner of its inaugural exhibition Pour la suite du monde when the new building opened on Sainte-Catherine Street. Several months before this event, the institution had acquired Le récit d’A. As one of the off shoots of ACT UP, Gran Fury built a certain activist image through interventions in magazines and on banner ads and buses. In Montréal, the collective produced a poster that superimposed the American flag and the Quebec flag, creating a hybrid visual object onto which was added “je me souviens” (“I remember”), as well as some statistics on the number of AIDS-related deaths in the United States, and a message about prevention. In hijacking the motto that appears on licence plates of Quebec vehicles, Gran Fury wanted to encourage the Canadian population not to become indifferent by reproducing the failings of the American ‘management’ of the crisis. Retrospectively, the members of the collective came to the conclusion that the intervention had failed in its aim because the Quebec public had been side-tracked by the spectral presence of the project of Quebec sovereignty at the expense of the work’s actual content.[18] This intervention therefore took place too late, as though political inertia had reigned in Montréal since the 1989 conference.

When the touring exhibition From Media to Metaphor: Art about AIDS, organized by Robert Atkins and Thomas Sokolowski, and circulated through New York’s Curators International, was held at the Musée d’art contemporain, the museum’s curator Réal Lussier presented Le récit d’A as a ‘local’ response. The exhibiting artists included a number of established and renowned figures including Gran Fury, General Idea, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Keith Haring, Robert Mapplethorpe and David Wojnarowicz, among others. This exhibition brought together predominantly American works that would become part of the canon, and certain among them, such as Nicholas Nixon’s sensationalist photographs, had previously been subject to strong criticism in the United States.[19] Le récit d’A was shown on a loop near to Mark Leslie’s photographic book/series photography series Living and Dying with Aids (1992) and Anne Golden’s video Les autres/women and AIDS (1991). Leslie chronicled his day-to-day experience of living with AIDS through self-portraits accompanied with a detailed handwritten text, almost like a medical history. Les autres/women with AIDS was one of the first documents about prevention made in Quebec to be aimed solely at women. Unlike Lise Bonenfant and Marie Fortin who, in Le sida au féminin (1989) had given a voice to HIV-positive women, Golden put together interviews – in French and English – with women who were HIV-negative. Some of them were collaborators – artist Charline Boudreau and curator and author Allan Klusaček – and others were members of community groups, such as the Haitian activists GAP-sida. Having acquired Le récit d’A following the exhibition, the museum didn’t screen the work again until the summer of 1994, the year of Valiquette’s passing, at an outdoor event co-organized by the opera company Chants libres, on Sainte-Catherine Street’s plaza.

In its posthumous trajectory, Le récit d’A was shown alongside other videos that, through their proximity, created thematic constellations more or less aligned with Valiquette’s own discourse. In certain programmes, its formal qualities are highlighted, while at other times Small’s voice is forefronted at the expense of Valiquette’s, the work becoming de facto a documentary about homosexuality and AIDS in the early 1990s. Less frequently, Le récit d’A appears alongside women artists’ works and, even more rarely, with testimonies by HIV-positive women.[20]

During her lifetime, most reviews of Valiquette’s work where published as newspaper articles. In an essay written in 1996, (above-mentioned) Nadeau offers a very complex and significant commentary on Valiquette’s work. However, she focuses on Le singe bleu, while situating Le récit d’A as a first hesitant attempt of a speech act.[21]

The article was also published in English in 2000.[22] From 1994 to 2014, Nadeau was a professor at Concordia University and, from 1994, she alternated with Waugh in delivering the course HIV/AIDS: Cultural, Social, Scientific Aspects of the Pandemic. She added Valiquette’s corpus to the already canonized video in English language about HIV/AIDS that were being studied. In her thesis of 2000, Maria Nehgeh Mensas, also a member of this group of academics at Concordia University (she was then a teaching assistant), placed Le récit d’A at a transitional moment in the Quebec media’s treatment of the crisis during the early 1990s and, simultaneously, at a time when the francophone voices of HIV-positive Québécoises women began to be heard.[23] In 2008, another group of researchers led by Nengeh Mensah gathered the testimonies (already in circulation) of HIV-positive individuals in Quebec. They produced a compilation of extracts from videos, television programmes and documentaries from different periods. Le récit d’A featured in its entirety.

Le récit d’A and Extenderis are distributed by Vidéographe, which became the rights holder in the absence of an executor of the will in 1994. The National Film Board distributes Le singe bleu.

The addition of videos about HIV/AIDS to Vidéographe’s collection was halted at the end of the 1990s. Since then, there has been a decline in activism and the production of works by HIV-positive artists; however, to stop there, on this statement about the dearth of contemporary testimonies, would be to locate the virus in a time capsule, while it continues to affect lives. In 2013, together with Ian Bradley-Perrin, artist Vincent Chevalier made a poster entitled Your Nostalgia is Killing Me, which identifies the phenomena of fetishism for the 1980s and 1990s – in their view, a ‘gentrification’ of memory with many harmful effects. It portrays an adolescent’s bedroom decorated with posters of responses by artists and the media to the crisis, the best and worst, which, once extracted from their original context and viewed only stylistically, at the surface level, become devoid of meaning.[24] In an interview given to Visual AIDS in 2013, Chevalier said that this rehashing of the cultural tropes of this period impedes us from considering other forms of thinking and of discourse about the epidemic.[25]

In 2014, curator José Da Silva presented Le récit d’A at the Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, with short films and videos representative of the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, using the title of Chevalier and Bradley-Perrin’s poster.[26] Valiquette was included, for the first time since 1990, in an international chronology of works about HIV/AIDS (along with Chevalier, Mike Holbloom, Tom Kalin, Rosa von Praunheim, Marlon Riggs, David Wojnarowicz, and Phil Zwickler, among others).

The history of the burgeoning of moving image practices about HIV/AIDS in Quebec during the 1990s has also been written about outside of Canada. In 2016, Andrew Gordon Bailey submitted his doctoral thesis at the University of Leeds, which offers the only comparative survey of film and video production in Quebec about the epidemic before access to antiretroviral therapies.[27] In it, Le récit d’A is the subject of a long analysis. In a paper given in 2021, Elliot Evans, of the University of Birmingham, compared Valiquette’s works and La pudeur ou l’impudeur (1992) by Hervé Guibert, in order to highlight the specificity of francophone cultural contexts (Québécois and French) in which a ‘visual language’ of HIV/AIDS is articulated.[28] My conversation with Conal McStravick also changes the course of the reception of Le récit d’A beyond national borders, as well as the Anglo-American hegemony of discourse.

After the screening at the Cinémathèque, we attempted, over numerous discussions, to define more precisely the point of convergence between the works by Stuart Marshall and Valiquette, beyond our respective texts. Certain comparisons are based on unusual parallels, such as those that, sometimes, justify the cohabitation of incomparable statements in a programme based solely on shared formal characteristics of the works. McStravick pointed out to me that the beginning of Le récit d’A, with its scenes of the tram in San Francisco, strangely echoes the travelling shots in a car of The Streets Of.., a video shot by Marshall in the same city in 1979. The resemblance is purely coincidental (it is highly unlikely that Valiquette had seen the video). However, if we watch these works one after the other, they show two moments in the history of San Francisco: the 1970s and the end of the 1980s, during which the gay population of the neighbourhood Castro was decimated, as well as the year 1990 when Valiquette went there to meet some ‘survivors’, as she put it. The commonalities between A Journal of the Plague Year (After Daniel Defoe) and Le récit d’A rest more directly on the fact that their respective inaugural exhibitions, with a five-year interval, belong to a timeline of HIV/AIDS that speaks of the late reaction of the Montréal art field to the crisis. Marshall’s installation, A Journal of the Plague Year (After Daniel Defoe), presented at Vidéo 84, was the first work about the epidemic seen in Montréal, while Valiquette’s video broke the ‘silence’ of Québécois artists since the beginning of the 1980s, when the virus was identified.

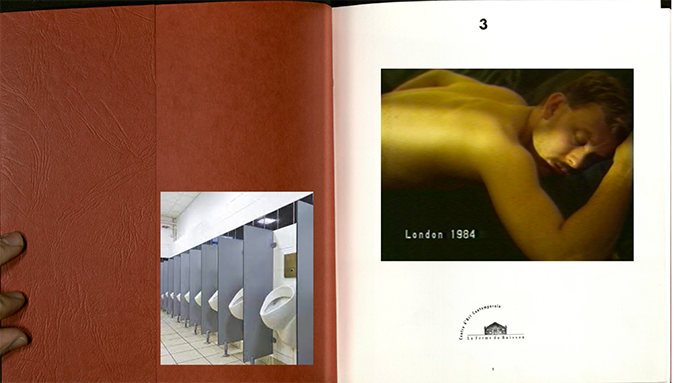

At Optica in 1984, A Journal of the Plague Years (After Daniel Defoe) comprised a series of five small monitors encased in the walls, in a structure resembling bathroom cubicles. Two monitors played extracts from filmic journals made in 1979 and 1984 (the dates are shown at the bottom of the screen) depicting the locus of Marshall’s daily life in long takes (his office, his bed, with his partner’s body) and the pages of British tabloid newspapers covering the beginning of the AIDS crisis in a sensational and homophobic manner. A third monitor showed segments filmed in different parts of Germany, evoking (again, with dates at the bottom of the screen), the persecution of homosexuals during the Third Reich. Graffiti and quotes from documentary sources used by Marshall covered the walls, offering fragments of context, similar to captions under photographs.

McStravick and I discussed the absence of a soundtrack in A Journal of the Plague Year (After Daniel Defoe), which resonated with the silence of the 1980s that Valiquette would have broken. Gay historian and critic René Payant organized a symposium at Vidéo 84 on the theme of description and wrote a text about the exhibited installations while sticking to a strictly formal analysis of Marshall’s work.[29] Payant died of AIDS in 1987, without ever publicly saying anything about the virus. The same year, Avram Finkelstein, Brian Howard, Oliver Johnston, Charles Kreloff and Chris Li (later Gran Fury) carried out an intervention equating silence with death (Silence = Death), adopting the pink triangle as a symbol of resistance. It was a necessary gesture, and the phrase is still used today as a slogan of solidarity amongst pwas. However, as Lee Edelman has stated, conflating the difficulty of responding to power through language with the avoidance of action is misleading.[30] At the time, in the mid-1980s, there was often a gulf between the will to speak and the ability to do so, which some wouldn’t cross, by fear of becoming even more exposed to homophobia and social death, before physical death.

I would like to imagine that if Payant were alive in 1990, he would perhaps have seen Le récit d’A and recognized in the voices of Valiquette and Small an experience intertwined with his own…

It is sometimes necessary to offer these speculative or improbable fictions, especially when the archives are lacking and we are left, as in this case, with a void. In doing so, authors and artists who have never met each other can ‘dialogue’ in a posthumous space through these video programs, these texts that we write despite it all (at the risk of speaking too much or too little for those who are absent).

Conal and I have already put Le récit d’A in dialogue with other works (for example those of Sandra Lahire), and the list below, providing an exhibition history of the video from 1990 to 2022 doesn’t close the parenthesis. By browsing it, one can also perceive the blank spaces between each screening, summoning fragments of a chronology of art and HIV/AIDS in Quebec in an incomplete way, and episodes, which, for lack of being able to say everything, I have completely omitted.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

6 – 9 December 1990, Cinéma Parallèle, Montréal.

Le récit d’A was shown with Ilandsis by René Roberge (1990) and Soi sage, ô ma douleur (et tiens-toi plus tranquille) by Charles Guibert and Serge Murphy (1990), as part of a program of works made during the year 1990 and co-produced by Vidéographe.

Image & Nation gaie et lesbienne : Festival international de cinéma et de vidéo de Montréal, 1990, Goethe Institut, Montréal.

Silence, elles tournent, 5 – 15 June 1991.

Esther Valiquette won the Audience Award for Le récit d’A.

Revoir le sida, Maison de la Culture Frontenac, 20 June 1991.

Le récit d’A was shown on the periphery of this multidisciplinary event organized by Diffusion gaie et lesbienne (René Lavoie and Allan Klusaček).

Daniel Carrière, “Démystifier le mal”, Le Devoir (21 June 1991), p. B-7.

Article about Le récit d’A.

Paul Cauchon, “Voir le sida au-delà des barrières psychologiques”, Le Devoir (14 June 1991), p. B1, B2.

Article about the event Revoir le sida.

Vidéoparc, 21 August 1991, Théâtre de Verdure, Parc La Fontaine.

Le récit d’A was included in a programme of female artists’ videos curated by Anne Golden and Cecil Castelluci for the Groupe Intervention Vidéo (GIV).

Daniel Carrière, “Un vidéoparc féministe au Théâtre de Verdure”, Le Devoir (19 August 1991), p. B12.

From Media to Metaphor: Art about AIDS, an exhibition organized by curators Robert Atkins and Thomas Sokolowski for Independent Curators Incorporated in New York in 1991 and shown at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, 29 October 1992 to 3 January 1993.

The local iteration of the exhibition, coordinated by curator Réal Lussier, comprised a selection of works by Montréal artists: Valiquette’s Le récit d’A, Anne Golden’s Les autres/Women and AIDS/HIV (1991) and Mark Leslie’s book of photographs Dying with AIDS/living with AIDS (1992).

3 – 6 December 1992, Cinéma parallèle, Montréal.

Le récit d’A was presented with Sehnsucht nach Sodom, by Hanno Baeth (1989), as part of a program organized by Vidéographe. Hanno Baeth’s work is also included in Vidéographe’s collection.

Daniel Carrière, “Le courage du désespoir”, Le Devoir (3 December 1992), p. B-4.

Stan Shatenstein, “Vision of a tragedy: Esther Valiquette uses her artist's eye to explore a deadly disease”, The Gazette (1 March 1993), p. F-3.

Beyond Loss: Two Voices, Out on Screen, Vancouver 6th Annual Lesbian and Gay Film Festival, 24 July 1994, Video Inn, Vancouver.

Le récit d’A was screened with Cancer in Two Voices by Lucy Massie Phoenix (1994) in this program curated by Maureen Bradley.

6 August 1994.

Le récit d’A was shown on TV5 at midnight, as part of a television show about video art entitled Kaléidoscope.

Téléguide progrès dimanche, w/c 31 July 1994.

Ô Arts Électroniques !, 30 August to 3 September 1994, Musée d’art contemporain, Montréal.

Le récit d’A was part of a program of videos from Quebec, Canada and around the world from the museum’s collection. It was screened outside, on the public square facing Sainte-Catherine Street. The event was co-organized by the opera company Chants libres.

Christine Ross, “Conflictus in Video”, Parachute, nº 78 (April, May, June 1995), p. 20-27.

Esther Valiquette passed away on 8 September 1994.

Marie-Michèle Cron, “Une journée sans art”, Le Devoir (1 December 1994). p. B10.

Dispersions identitaires : vidéogrammes récents du Québec = Identity Dispersions: Recent Videos from Quebec, Art Gallery of Ontario = Musée des beaux-arts de l’Ontario, Toronto, 25 January to 26 March 1995.

Le récit d’A was shown in an exhibition of Québécois video organized by Christine Ross. Catalogue.

Chantal Nadeau, “Esthétique scientifique et autobiographie dans l’œuvre d’Esther Valiquette”, Protée, vol. 24, nº 2 (Autumn 1996), p. 35-43.

Reconfigured Histories, Remembered Pasts, 6 November to 19 December 1997, Gallery of the Saidye Bronfman Centre for the Arts, Montréal.

In this exhibition organized by Robert W.G. Lee, Le récit d’A was shown alongside works by Stephen Andrews, Michael Balser, Charline Boudreau, Andy Fabo, Anne Golden and Regan Morris. The catalogue included texts by the curator and Chantal Nadeau.

Bernard Lamarche, “Art et sida”, Le Devoir (13-14 December 1997), p. B12.

Espaces intérieurs : Le corps, la langue, les mots, la peau, 20 April to 10 June 1999, Passage de Retz, Paris.

Le récit d’A was included in an exhibition of works by Quebec artists organized by Louise Déry and Nicole Gingras during Printemps du Québec en France. Catalogue.

Maria Nengeh Mensah, Anatomie du visible. Connaître les femmes séropositives au moyen des médias, thesis presented at the Department of Communication Studies, Concordia University, February 2000.

In 2001, Le récit d’A was shown in DVD format with Comment vs dirais-je by Louis Dionne (1995) as part of a program entitled “Séropositivité” curated by Vidéographe.

Jean-Philippe Gravel, “Compilation du Vidéographe : créer comme on respire”, Ciné-Bulles, vol. 19, nº 3 (Summer 2001), p. 48-50.

Thomas Waugh, The Romance of Transgression in Canada: Queering Sexualities Nations Cinemas, Montréal, Kingston, McGill-Queens University Press, 2006.

VIHsibilité, a day-long conference on AIDS, testimony and the media, 11 December 2009, Université du Québec, Montréal. Le récit d’A was shown with Mike Holbloom’s Letter from Home (1996), as part of a program that ran in parallel with the conference.

Fictions limites, Festival Instants vidéo numériques et poétiques, 7 – 17 November 2013, Friche de belle de mai, Marcheille.

Le récit d’A was shown as part of a program of Quebec video curated by Claudie Lévesque and Fabrice Montal. Catalogue.

Your Nostalgia is Killing Me, Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, 26 November to 1 December 2014, Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane.

Le récit d’A was included in a program of film and video works about HIV/AIDS from 1985 – 2014, curated by José Da Silva from the Australian Cinémathèque. See this webpage for a list of works: https://www.qagoma.qld.gov.au/cinema/program/your-nostalgia-is-killing-me

Chantal Dupont, 19 February to 18 April 2015, Dazibao, Montréal.

Le récit d’A was included in a program of works by artists whose practices are thematically or formally linked to work by video maker Chantal Dupont.

See this webpage for a list of works: https://dazibao.art/exposition-chantal-dupont

In 2015, Le récit d’A was included in a DVD compilation entitled VIHsibilité (1985-2000), curated by Testimonial Cultures (Gabriel Giroux, Maria Nengeh Mensah and Thomas Haig).

The compilation comprises the testimonies of HIV positive individuals as shown on television shows, films and videos between 1985 and 2000 in Quebec.

Gabriel Giroux, Maria Nengeh Mensah and Thomas Haig, Rapport d’activités de recherche sur les archives du groupe Cultures du témoignage, 2015.

Andrew Gordon Baley, The Representation of HIV/AIDS in Québec Cinema, 1986-1996.

PhD thesis submitted to the School of Languages, Cultures and Societies, The University of Leeds, in 2016.

Queer Autocinema from Québec: From the Sexual Revolution to AIDS, 15 June 2017, Queen Mary University of London Theatre. Le récit d’A was shown with À tout prendre by Claude Jutra (1963) as part of a program curated by Jordan Arsenault of Mediaqueer.

Produit du terroir : vidéos de femmes et vidéos queer de 1990, Rencontres internationales du documentaire de Montréal, 11 November 2018, Cinémathèque québécoise, Montréal.

Le récit d’A was shown along with Prowling by Night from Five Feminist Minutes by Gwendolyn & Co, Bodies in Trouble by Marusya Bociurkiw (1990), Exposure by Michelle Mohabeer (1990), We’re Here, We’re Queer, We’re Fabulous by Maureen Bradley and Danielle Comeau (1990) and AnOther Love Story by Debbie Douglas and Gabrielle Micallef (1990), as part of a program curated by Jordan Arsenault of Mediaqueer.

Fine Local Product: Women-made + Queer Shorts from 1990, Inside Out, Ottawa LGBT film festival, 12 November 2018, Musée des beaux-arts du Canada, Ottawa.

This is the same program as above.

Son propre visage en partage, 23 May 2018, Dazibao, Montréal.

Le récit d’A was presented as part of a video program on the theme of faciality, curated by Lucie Szechter for Dazibao, in collaboration with Vidéographe.

See the following webpage for a list of works:

https://vitheque.com/en/programmations/sharing-ones-own-face

Les vidéographes : Le gai savoir, 25 November 2021, Cinémathèque québécoise.

Le récit d’A was shown as part of a program of works from Vidéographe’s collection curated by Luc Bourdon.

See the following webpage for a list of works:

https://www.videographe.org/en/activity/les-videographes-a-la-cinematheque-quebecoise/

Elliot Evans, The Visual Language of HIV/AIDS: Considering the Films of Hervé Guibert (France) and Esther Valiquette (Québec), 3 March 2021. Communication by the Faculty of Arts and Humanities, King’s College, London. See the event webpage https://www.kcl.ac.uk/events/the-visual-language-of-hivaids-considering-the-films-of-herve-guibert-france-and-esther-valiquette-quebec

Cristina Robu, La mise en récit du corps malade de l’autre dans la littérature et le cinéma québécois contemporains : matière à (d)écrire, PhD thesis submitted to the

Department of French and Italian, Indiana University, August 2022.

VIdéoH / HIVideo (Autres) réponses culturelles : le VHI/sida et la vidéo à Montréal (1984-1990), 1 August 2022, Cinémathèque québécoise, Montréal.

Le récit d’A was shown as part of this program and a round table. Vincent Bonin responded to Le récit d’A and Conal McStravick responded to The Journal of the Plague Year (after Daniel Defoe) by Stuart Marshall (1984). The discussion was moderated by Maria Nengeh Mensah.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Footnotes

[1] Jean-Claude Marineau, “Le singe bleu d’Esther Valiquette”, Parachute, nº 69 (January, February, March 1993), p. 40.

[2] Daniel Carrière, “Démystifier le mal”, Le Devoir (21 June 1991), p. B-7.

[3] Claudio Zanchettin, “L’accident vital, entrevue avec Esther Valiquette”, c. 1993, the author’s own website: http://www.trempet.it/Conjonctures/Parauteur/claudiozanchettin.htm.

(consulted on 10 September 2022). The interview can be downloaded in pdf format at this address but it remains incomplete.

[4] Several documents published by ACT UP, AIDS ACTION NOW and RÉACTION SIDA, including the Montréal manifesto, are available on the website AIDS Activist Project:

https://aidsactivisthistory.omeka.net

(consulted on 19 September 2022). For the conference’s impact after 1989, see Gabriel Girard and Alexandre Klein, “Les leçons de la conférence sur le sida de 1989”, Le Devoir, 5 June 2009.

Available online:

(consulted on 19 September 2022).

[5] Chantal Nadeau, “Esthétique scientifique et autobiographie dans l’œuvre d’Esther Valiquette”, Protée, vol. 24, nº 2 (Autumn 1996), p. 35-43.

[6] Sandra G. Boodman, “AIDS survivors beating the odds”, The Washington Post (8 February1988). Available on the Washington Post website:

(consulted on 19 September 2022).

Sandra G. Boodman, “After 7 years, San Francisco learned to live with AIDS”, The Washington Post (7 April 1988). Available on the Washington Post website:

(consulted on 19 September 2022).

[7] KQED special report, by Randy Shilts, broadcast 14 December 1989. Available on the Bay Area Television Archive website:

https://diva.sfsu.edu/collections/sfbatv/bundles/190109

(consulted on 19 September 2022).

[8] Ross Chambers, Facing it: AIDS Diaries and the Death of the Author, The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 1998.

[9] Laura U. Marks, “Loving a Disappearing Image”, Cinémas: revue d'études cinématographiques / Cinémas: Journal of Film Studies, vol. 8, nos 1-2 (1997), p. 93-111.

[10] On this documentary, see Paula A. Treichler, “Beyond Cosmo: AIDS, Identity and Inscriptions of Gender”, Camera Obscura, vol. 10, nº 28 (1992), p. 20-77.

[11] Thomas Waugh, The Romance of Transgression in Canada: Queering Sexualities Nations Cinemas, Montréal, Kingston, McGill-Queens University Press, 2006, p. 284.

[12] I first became aware of Revoir le sida through Anne Golden’s work, Les autres/Women and AIDS (1991), which was mentioned in an interview with Klusaček. I then found Paul Cauchon’s review, “Voir le sida au-delà des barrières psychologiques”, Le Devoir (14 June 1991), p. B1, B2. I wasn’t able to find the list of Quebec artists who took part in the exhibition, with the exception of Valiquette.

[13] A Leap in the Dark: AIDS, Art and Contemporary Cultures, under the direction of Allan Klusaček and Ken Morisson, Véhicule Press, Artexte, Montréal, 1992.

A pdf version is on the Artext website:

https://e-artexte.ca/id/eprint/6455/1/Leap_in_the_Dark_complete2022.pdf

(consulted on 19 September 2022).

[14] Daniel Carrière, “Démystifier le mal”, Le Devoir (21 June 1991), p. B-7.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Thomas Waugh, op. cit., p. 308.

[17] Throughout the 1990s, art historian Johanne Lamoureux wrote about the reinforcing of this linguistic and cultural divide in the field of visual arts in Canada. See: Seeing in Tongues: A Narrative of Language and Visual Arts in Quebec/Le bout de la langue. Les arts visuels et la langue au Québec, Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, Vancouver, 1996.

[18] See Jack Lowe, It Was Vulgar & It Was Beautiful: How AIDS Activists Used Art to Fight a Pandemic, New York, Bold Type Books, 2022. He addresses the failure of Gran Fury’s project on page 355.

[19] See Anne Whitelaw’s review, “Exhibiting AIDS”, Parachute, nº 73 (January, February, March 1994), p. 53-55.

[20] This was the case during Beyond Loss: Two Voices, Out on Screen, Vancouver 6th annual Lesbian and Gay film festival, 24 July 1994, Video Inn, Vancouver. Le récit d’A was shown with Cancer in Two Voices by Lucy Massie Phoenix (1994) in a program curated by Maureen Bradley.

[21] Chantal Nadeau, “Esthétique scientifique et autobiographie dans l’œuvre d’Esther Valiquette”, op., cit., p. 39.

[22] Chantal Nadeau, “Blue(s) Valiquette: AIDS, Autobiography, and Arty Science in the Works of Esther Valiquette”, Lonergan Review, vol. 6 (2000), p. 216-237.

[23] Maria Nengeh Mensah, Anatomie du visible. Connaître les femmes séropositives au moyen des médias, thesis presented to the Department of Communication Studies, Concordia University, February 2000.

[24] See the Visual AIDS webpage dedicated to the poster, accompanied by a manifesto:

https://postervirus.tumblr.com/post/67569099579/your-nostalgia-is-killing-me-vincent-chevalier (consulted on 19 September 2022).

[25] “As we canonize certain producers of culture, we are closing space for a complication of narratives”, Visual AIDS, 10 December 2013.

https://visualaids.org/blog/as-we-canonize-certain-producers-of-culture-we-are-closing-space-for-a-comp (consulted on 19 September 2022).

[26] Your Nostalgia is Killing Me, Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, 26 November to 1 December 2014.

[27] Andrew Gordon Baley, The Representation of HIV/AIDS in Québec Cinema, 1986-1996. Doctoral thesis submitted to the School of Languages, Cultures and Societies, University of Leeds, 2016.

[28] Taken from a promotional text “The Visual Language of HIV/AIDS: Considering the Films of Hervé Guibert (France) and Esther Valiquette (Québec)”, posted online 3 March 2021 by Faculty of Humanities du King’s College, London.

[29] René Payant, “Sites de complexité”, in Vidéo, under the direction of René Payant, Montréal, Éditions Artexte, 1984, p. 127-131.

[30] Lee Edelman, “The Plague of Discourse, Politics, Literary Theory and ‘AIDS’”, in Homographesis: Essays in Gay Literary and Cultural Theory, New York, Routledge, 1994, p. 79-91. Edelman poses the following question about the presupposition that speech and the simple statement of facts about illness would, de facto, be performative and therapeutic: “What discourse can this call of discourse desire? Just what is the discourse of defense that could immunize the gay body politic against the opportunistic infection of demagogic rhetoric?”, p. 88.

AIDS and video in Montreal (1984-1990): Stuart Marshall’s Journal of the Plague Year (After Daniel Defoe), 1984

Conal McStravick

Journal of the Plague Year (After Daniel Defoe) (1984) is one of a suite of highly influential AIDS activist video works made by the UK artist, activist, writer, educator, curator, and arts and AIDS community organizer Stuart Marshall. Born in Manchester, England, in 1949, Marshall died in London in 1993, of an AIDS-related illness.[1]

Journal was exhibited as part of Vidéo 84, in Montreal, at the artist-run centre Galerie Optica. Its exhibition trajectory continued over three decades, with the work being re-exhibited in Montreal, London, and New York in 1984–85, in Oxford in 1990, in Leeds in 1991 and at Ferme du Buisson, near Paris in 1993 and, finally, once more in London in 2016. Vidéo 84—also known as Rencontres Vidéo Internationales de Montréal—organized by Andrée Duchaîne, comprised an exhibition of eighteen international artists from eleven countries across eight Montreal galleries and arts venues. The exhibition included artists such as Dara Birnbaum, Mary Lucier, the Dutch artist Servaas, and General Idea. It was accompanied by a symposium organized by art historian René Payant.

Writing in AIDS TV, the key survey of US and, in particular, New York AIDS-activist video of the period, Alexandra Juhasz cites Marshall’s AIDS video oeuvre as foundational in establishing an “alternative AIDS media.”[2] More recently, Roger Hallas examines how Marshall and the AIDS moving image archive have the capacity to “bear witness” to the histories, cultures, and politics of AIDS, then and now.[3] Aimar Arriola suggests, further, that Marshall’s expanded “queer archive” reactivates past struggles in the present and for the future, and quotes Marshall as remarking that “AIDS offers the possibilities to build alliances that do not yet exist.”[4]

First, what was Journal of the Plague Year, and how did it come to appear in Montreal?

Journal of the Plague Year is a completely silent installation—a notable occlusion for Marshall, who was trained as a sound artist and musician. Marshall’s sound and video milieu emerged out of a transatlantic education, beginning at Hornsey College of Art, in London, where he took part in a 1968 student sit-in. Later, at the Newport College of Art, in Wales, and at Wesleyan University, in Connecticut, Marshall came into the sphere of influence of certain vanguard musicians such as Gavin Bryars and, ultimately, would become a favoured student of Alvin Lucier, at Wesleyan. Marshall’s was a sound milieu in a post-Cageian mould, in which silence was both material and political.[5]

In Journal, on an imposing eight-metre wall, some partitions, which recall those that separate the urinals in public washrooms, frame several sunken video monitors. Within each partition, and surrounding each twelve-inch monitor screen, is the enlarged text of a quotation on the subject of AIDS and its wider context. Expanding from the earlier Kaposi’s Sarcoma: A Plague and Its Symptoms (1983), the various quotations are sourced from historical, medical, media, and graffiti sources, and reproduced in newspaper type fonts or as handwritten texts. Each was chosen to illuminate the content and context of the corresponding video.[6]

The work’s title is derived from author and journalist Daniel Defoe’s 1722 book of the same name, which Defoe styled as a first-person eyewitness account of the Great Plague of 1665–66, in London and its environs. Marshall would later explain:

The expression “The Gay Plague” was formulated during the first two waves of homophobic AIDS reporting in the English tabloid press in 1983 and 1984. As a response to this disgusting journalism I made a work which spoke about the experience of AIDS from within the gay community and in order to emphasize this insider’s view I titled the work after Daniel Defoe’s account of the Black Death.[7]

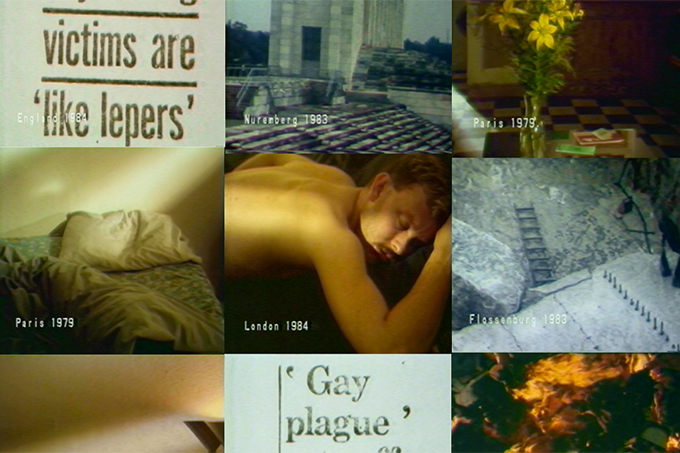

Surviving documentation of Marshall’s installation taken at Vidéo 84[8] offers a historical frame of reference for contextualizing the media representation of AIDS as a kind of “history of the present,”[9] to borrow Michel Foucault’s concept. The videos reveal three broadly contemporary and three historic settings: “Paris, 1979,” “London, 1984,” and “England, 1984” as well as “Flossenbürg, 1983,” “Nuremberg, 1983,” and “Berlin, 1933.”

Marshall’s spare, locked-off video shifts abruptly to a handheld camera roaming amidst a chic, empty apartment—no doubt Marshall’s own—figuring “Paris, 1979.” In “London, 1984,” viewed from both sides, we see a young, white, man sleeping. His appearance, , possesses the archetypal “clone” look of the London gay scene of the early to mid-1980s. The framing of the figure is intimate, and, in fact, the sleeping man is Marshall’s boyfriend Steve.[10]

In a review of the German New Wave classic Taxi Zum Klo (1980) by Frank Ripploh, which translates roughly as “Taxi to the Loos,” Marshall acknowledges the

different forms of non-monogamous emotional and sexual relationships gay men are attempting in order to best suit their needs, or of the complex and difficult political analyses they are attempting of those areas of experience that patriarchal heterosexism has termed “personal.”[11]

In clear contrast, on Marshall’s “England, 1984” video monitor is a montage of phobic tabloid headlines about AIDS—indications of an increasingly homophobic and punitive public sphere delineated by compulsory patriarchal heterosexuality. In 1990, as though to affirm this, Marshall described the work as counterposing “representations derived from both the public and private sphere to demonstrate the struggle to determine the meanings of homosexuality.”[12]

As such, Marshall’s analysis hovers over the contradiction embedded in the decriminalization of sex between men in England and Canada enshrined, in the former case, in the 1967 Sexual Offences Act,[13] and similarly, in the latter, in the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1969.[14] At the time, these legislations ruled that sex was only legal if it happened in private and between two individuals over the age of 21. Marshall’s washroom architecture points to other arenas and battlegrounds of gay male sexuality and MSM sex: places and people supposedly liberated, yet noticeably vulnerable to police surveillance, entrapment, and criminalization.

—————

For Journal of the Plague Year, Marshall juxtaposed the formal innovations of video installation works—such as Beryl Korot’s four-channel video installation Dachau, 1974,[15] a multi-screen presentation that Korot herself filmed at the former German concentration camp—with his own collage of found texts and original films and videos.

Three further, historical settings—“Flossenbürg, 1983,” “Nuremberg, 1983,” and “Berlin, 1933,” all of them shot, in the present, on Super-8 film—relate directly to Germany in 1933, the year in which the Nazis came to power. These settings include images of the quarries at the former Flossenbürg concentration camp and the ruins of the Nazi parade ground at Nuremberg—the latter built of granite quarried at Flossenbürg using forced labour, including that of “pink triangle” homosexual prisoners.

In the final screen, titled “Berlin, 1933,” a burning pyre of books, images, and photos represents the research library and archives of the German sexologist and sexual reform campaigner Magnus Hirschfeld, destroyed in a night-time raid on Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexology followed by a Nazi book-burning spectacle in the Berlin Opera Square. Against the contemporary context of calls to censor AIDS literature, or, worse still, threats of quarantine or imprisonment for PWAs (people with AIDS), Marshall’s diegesis establishes a link between the destruction of Hirschfeld’s sexology archive and library, and the imprisonment and forced labour suffered by homosexuals in Nazi Germany.

In 1984–85, 1990-1991, 1994, and 2016, Journal of the Plague Year was exhibited in the UK, France, and North America. In its first year, it was exhibited, in quick succession, at Vidéo 84 in Montreal; at Cross Currents, Royal College of Art, London; and in single-screen format as part of the exhibition Difference: On Representation & Sexuality, New Museum, New York.

Meanwhile, Marshall continued to adapt the textual content. In the 1984 version, a graffiti text framing the “London, 1984” sleeping-man monitor reads “AIDS KILLS QUEERS.” In the 1990 and subsequent versions—leaving little to the imagination—this became: “AIDS: ARSE INJECTED DEATH SENTENCE.”

A more ambiguous text frames the “Paris, 1979” vignette: “It has now been two weeks and three days. His mother continues to try to enter the apartment. She threatens to call the police.” The “England, 1984” tabloid headlines are contrasted with a medical report: “Kaposi’s Sarcoma: an oncologic looking glass.”

The text for the “Berlin, 1933” monitor states: “This evening, stormtroopers took the contents of the Institute for Sexual Science to the Opera Square and with much celebration they set them alight.” Recalling the history of “pink triangle” homosexuals, the “Flossenbürg, 1983” and “Nuremberg, 1983” monitor texts read:

Eventually, I was taken to Flossenbürg. This is where the stones were dug and prepared for all of Hitler’s major building work. The work of quarrying, dynamiting, hewing and dressing, was extremely dangerous and arduous, and only Jews and homosexuals were assigned to it.

An exhibition text, clearly written by Marshall states: “It has taken over a hundred years for gay men to wrest away from the medical profession the right to define their sexuality. As a result of this most recent ideological articulation of disease and sexuality gay men are losing back to the medical profession the hard-won right to define their own sexuality.”[16]

Notwithstanding the clear and present media homophobia, a claustrophobic sense of growing surveillance and loss of autonomy within the gay community and, worse, the palpable threat of quarantine during the early days of the AIDS crisis, an intense medical gaze pervades the installation, evoking the weight of history and the suppression of past attempts at liberation. And yet, in and of itself, Marshall’s intervention, in its many versions and its forbidding, tactical silence, represents a site of activist cultural resistance against the oppression experienced by all communities impacted by AIDS and the stigma suffered by PWAs.

————

Journal of the Plague Year (After Daniel Defoe) was preceded by what was perhaps the first AIDS activist video in the global AIDS video archive: Marshall’s Kaposi’s Sarcoma: A Plague and Its Symptoms, which toured Canada in 1983 as part of a program of independent UK artists’ videos. This was followed by Stuart Marshall’s celebrated television documentary Bright Eyes, broadcast on Channel 4 television in the UK in late 1984, shaping a new kind of AIDS video activism—a signal work in the corpus of international AIDS video.

Journal and Kaposi’s Sarcoma deserve their places as part and parcel of Stuart Marshall’s media interventions during the earliest phase of the AIDS epidemic—at art galleries and in academia, through video art and community video networks, and in interviews on public access and network television. And, last but not least, these works speak to the story, one that is insufficiently told, of how Marshall moved through LGBTQ+ and AIDS art and activist networks in Canada and North America in the period 1983–84, and then continuously, through the 1980s and early 1990s, to become a noted figure in the world of LGBTQ+ and HIV/AIDS cultural activism in Canada, the UK, and internationally.

In a June 1983 televised interview recorded for Gayblevision, the Vancouver gay-and-lesbian cable television show,[17] we see Marshall filmed at the Video Inn, an artist-run centre in Vancouver. Here the artist is introduced as, “an independent video producer and writer based in London, who is involved in gay politics.”[18] He also discusses his new AIDS-related videotape, Kaposi’s Sarcoma.

On paper, Marshall was the official British representative for the touring program of workshops and screenings of UK artists’ videos mentioned earlier, an initiative funded by the British Council. In the interview, he discusses independent video production in the UK, the limited scope for video and LGBTQ+ content in the UK media, and the early response of the UK gay community to AIDS. Here, the latter part of the title of Kaposi’s Sarcoma is revealed as: A Plague and Its Symptoms. This, as Marshall—usually an unembarrassed Francophile—modestly notes, is “a quote from Artaud.”[19]

This statement is significant, as Marshall was an ardent French Theory-quoting art critic and video theorist, whose practice was embedded in recent UK and North American queer and feminist video. Prior to Journal, Marshall’s video works expanded from performance-to-camera, single-monitor works that referenced recent histories of conceptual and feminist video to works more experimental in form, with professional actors using televisual and agitprop theatre methods. These later works also saw the addition of direct quotations and hybrid scripts, with theoretical texts by Louis Althusser, Simone de Beauvoir, Michel Foucault, and Guy Hocquenghem.[20]

As such, Marshall’s theory of video as a “signifying” and “oppositional” medium was founded on a combination of Anglophone—particularly British—left-critical thought and queer media activist intentions, with Francophone cultural theory and criticism. The former catalyzed a demand for an alternative media at the heart of the UK Gay Liberation Manifesto, written in 1971, which identified the media as one of the shibboleths of straight society used to oppress gay people.[21] Marshall cited left-critical British media theory like that of Raymond Williams,[22] Stuart Hall,[23] and the Glasgow Media Group,[24] combining this with Francophone post-structural cultural theory such as Julia Kristeva’s so-called “semanalysis,”[25] which formulated culture at large as a field of semiotic, “signifying,” and psychoanalytically literate interpretation, in a manner that appealed to Marshall’s intellectual and practical methods.

In fact, tellingly, Marshall’s reference to Artaud comes directly from Guy Hocquenghem’s 1972 book Homosexual Desire, in which, speaking of syphilis, Hocquenghem observes:

Syphilis is not just a virus but an ideology too; it forms a fantasy whole, like the plague and its symptoms as Antonin Artaud analyzed them. The basis of syphilis is the phantasy fear of contamination, of a secret parallel advance both by the virus and the libido’s unconscious forces; the homosexual transmits syphilis as he transmits homosexuality.[26]

As Marshall goes on to explain in the interview, these phobic associations were clearly observable in the initial media response to AIDS, setting the stage for a similar but even more morbid signifying chain all too evident in international AIDS coverage. This moral equivalence between gay male promiscuity and death or disease, augmented by an association between gay male promiscuity and AIDS, was later represented by Marshall in his documentary Bright Eyes, through an exacting visual analysis of the homophobic tabloid media coverage of PWAs and AIDS. The repression encountered in this media precedent is mirrored in the medical, sexology-related, and criminal archives—a formula which Cindy Patton later summarized as “homosexuals=AIDS=death.”[27]

Marshall’s developing AIDS activist video project, its archival emphasis, and his conception of video as a signifying medium and, therefore, as a re-signifying practice, presaged Paula Treichler’s incipient conception of AIDS as an “epidemic of signification.”[28]

Although it appears, regrettably, that Kaposi’s Sarcoma is now lost, we may surmise from the precious Gayblevision footage that media analysis in this piece carried over into Marshall’s subsequent works: Journal of the Plague Year and Bright Eyes. With stills of newspaper headlines such as “Cancer, Poppers and Gay Men” and “Are Homosexuals Killing Themselves?” it is easy to concur with Marshall that, “the way that AIDS has been represented by the media is nothing more than a sophisticated form of queer bashing.”[29]

If we look to another parallel text in the Canadian AIDS archive, Marshall’s analysis in his early suite of AIDS works likely owes something to AIDS activist and PWA Michael Lynch’s article “Living with Kaposi’s Sarcoma,” published in 1982 in The Body Politic.[30] Here, Lynch’s portrait of Fred, a man living with AIDS in the form of Kaposi’s sarcoma, combines a historical, critical, and literary analysis, leading Lynch to identify AIDS as “a major setback to what we used to call gay liberation.”[31]

Like Hocquenghem’s texts, this article by Lynch grounds its analysis in the image of the homosexual as seen through an anti-homosexual criminal code, the medical model of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century psychology and sexology, and a countervailing, post-gay-liberation resistance to this pathologization—all themes that Marshall expanded upon in his AIDS activist works through the use of video, within an intertextual framework, to expose these histories and their resonance in the context of AIDS.[32]

—————

Together with Vincent Bonin, I have reflected on the palpable silence of Montreal art critic and art historian René Payant (1949–1987), who was a contemporary of Stuart Marshall’s. Payant edited the exhibition catalogue for Vidéo 84, published in 1986. Payant was openly gay, and positive, at a time when institutions were still homophobic. Despite writing on Marshall’s exhibition for the catalogue, Payant said but little about its contents. Perhaps this silence—which resonates both throughout Marshall’s silent installation and Payant’s text—acknowledges a space between the naming of a new virus (which we now call HIV) and the articulation of new forms of AIDS activism. Other things were felt, other things were lived in that time—those first years of the AIDS crisis—that remained, and perhaps still remain, unnamable.

In a January 1987 Artforum editorial titled “Esthetics and Loss,” which featured Marshall’s Bright Eyes, Edmund White stated as much:

If art is to confront AIDS more honestly than the media have done, it must begin in tact, avoid humor, and end in anger…. Avoid humor, because humor seems grotesquely inappropriate to the occasion. Humor puts the public (indifferent when not uneasy) on cosy terms with what is an unspeakable scandal: death.[33]

Although White’s pronouncements regarding the affect of AIDS activism were swiftly rebutted by Douglas Crimp, John Greyson, and others, Marshall presented a perhaps more nuanced ethos of silence two years later at the How Do I Look? conference, held at the Anthology Film Archives in New York.[34] There, Marshall delivered a paper, “The Contemporary Political Use of Gay History: The Third Reich,” in which he charted the appropriation, by the modern-day gay movement, of the pink-triangle symbol used to identify homosexual prisoners in Nazi concentration camps.[35]

For Marshall, the then-recent juxtaposition of an inverted pink triangle with the words “Silence=Death” in the Silence=Death/ACT UP poster campaign, although rightly to be lauded for its politics, ran the risk of overwhelming the emerging histories and testimonies of gays and lesbians who had survived the Nazi persecutions[36] and for whom the very opposite proposition—“Silence=Survival”—had arguably been the only means of survival.”[37] Writing more recently, Jack Halberstam has reframed Marshall’s critique of the pink triangle to recontextualize the figure of the gay fascist and other “silences” in queer epistemologies and praxis.[38]

At the time, in the UK and Quebec press, Jez Welsh and Christine Ross, respectively, captured the unique capacity of Journal of the Plague Year to bring together personal and polemical reactions from within the gay community in opposition to the media’s response to AIDS. In Parachute, Ross stated that “the artist’s activity is located between appropriation and architecture…. The installation adopts the form of a newspaper to unveil the anti-homosexual ideology conveyed through the media; and that it does so to challenge the viewer’s habitual media passivity.”[39] Writing for Performance, Welsh described a homophobic media using “disease or fear of disease as social control.”[40]

In his essay for the publication that accompanied the How Do I Look? conference, Marshall reveals his intention for his early AIDS activist video works:

This took the form of a collage of different historical discourses, images and meanings about homosexuality, taxonomy and disease…. A kind of collage, a series of temporal juxtapositions of textual units…. I chose this form because it allowed me to collide different historical episodes in such a way that the viewer would be presented with the problems of assembling their mutual relationships.[41]

Marshall concluded that although he did not intend “to draw a parallel between the AIDS epidemic and the Holocaust,” he nonetheless acknowledged “fears that the international lesbian and gay rights movement might suffer a fate in the 1980s similar to the eventual demise of the German movement in the 1930s, when it was completely destroyed by the Nazis.”[42]

After Journal of the Plague Year, Marshall’s television documentary Bright Eyes assumed greater cultural capital within Marshall’s body of work. It came to be included in major AIDS cultural activist surveys and AIDS video activist compilations, and was re-broadcast on cable television.[43]

In “AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism,” the genre-defining 1987 special issue of the arts journal October, queer art historian and AIDS activist Douglas Crimp designated Bright Eyes as a work at the nexus of “a critical, theoretical and activist alternative to the personal, elegiac expressions that appeared to dominate the art world response to AIDS.” Prompted by Marshall, Crimp affirms that, “AIDS intersects with and requires a critical rethinking of all culture: of language and representation, of science and medicine, of health and illness, of sex and death, of the public and private realms.”[44]