Fever Freaks

A detective is hired to find the original copy of a lost ancient book. The book recounts the tale of a plague. A form of radiation, unknown at the present time, activates a virus. The virus affects the sexual and fears centers in the brain and nervous system, fear is converted into sexual frenzies which are reconverted back into fear, the feedback leading in many cases to a fatal conclusion.

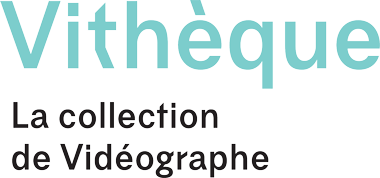

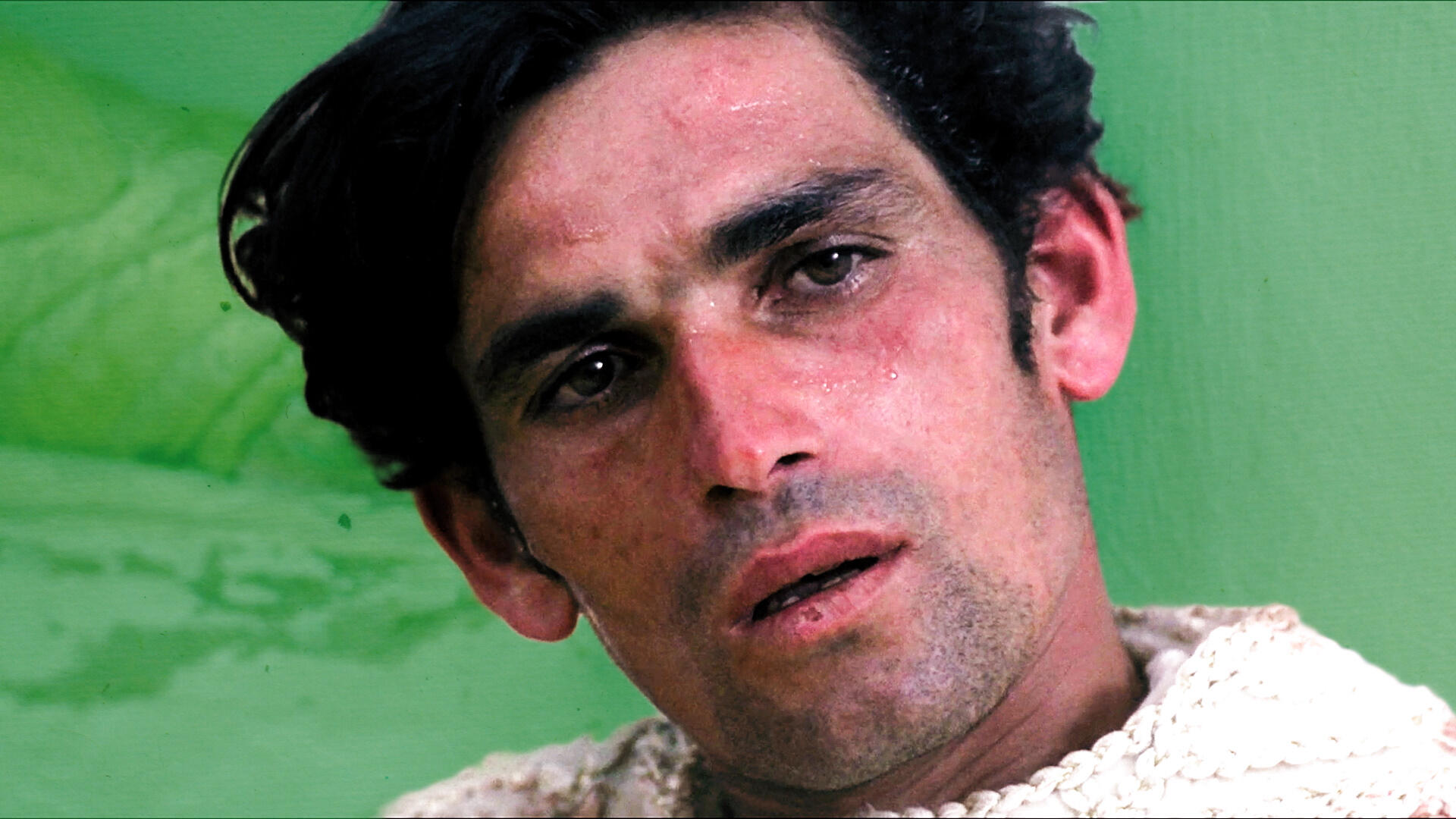

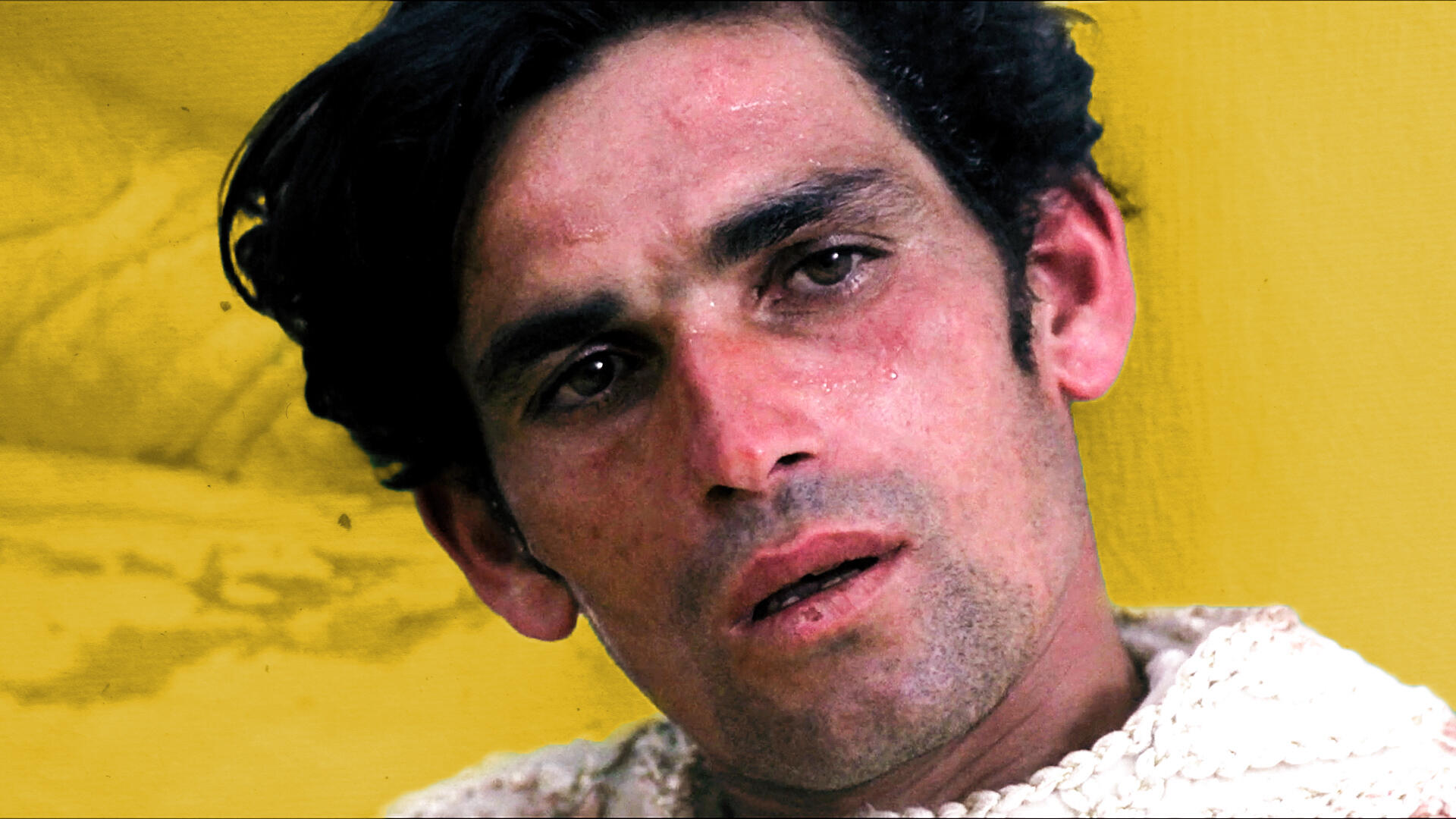

Fever Freaks manipulates and re-edits individual frames from Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1974 film Arabian Nights to illustrate a passage of William S. Burroughs’ 1981 book Cities of the Red Night.

Credits

Technical information

Documentation

Interview with Frédéric Moffet

How did Pasolini and Burroughs’ worlds come together?

It was a chance meeting. Two years ago, I was reading Cities of the Red Night by William S. Burroughs. One night during the same period, I watched Arabian Nights by Pier Paolo Pasolini. I thought to myself that one could probably re-edit Pasolini’s film to tell Burroughs’ story. The casting and locations were ideal. I continued reading. I became obsessed with a particular short passage, just a few sentences in a complex book with multiple storylines spanning millenniums. Burroughs describes lost ancient books that recount the story of a plague caused by a virus that transforms fear into sexual frenzy and then back again into into fear, the vicious circle often leading to fatal conclusions sending in fatalities. First published in 1981, Burroughs’ writing was prophetic. He is not describing the AIDS pandemic in Cities of the Red Night but it is impressive that he, the iconic queer junky, would imagine a virus that connects desire, disease and death at that moment in history. On a dare, I tried to adapt the passage that so affected me using footage from Arabian Nights. Burroughs and Pasolini have a lot in common. They were radical visionaries and provocateurs. They were unapologetically queer in a time when it was not tolerated. They had a taste for young street-wise hustlers and were both repulsed by bourgeois society. To the best of my knowledge they never met in person.

The visual evokes a feverish dream. How did you work the images and color?

I was very literal. I wanted to recreate the books that Burroughs had envisioned in Cities of the Red Night. They were picture books that used a strange color process to transfer three- dimensionalholograms onto tough translucent parchment-like material. He described the result as a poisonous miasma of color. To create the effect, I reworked each frame individually, cutting them up into layers, where I would alter the saturation and opacity, and add color mattes and scanned sheets of paper. It was a painstakingly tedious process. I am no professional animator so the result is wonderfully rough. I was also inspired by Paul Sharits’ 1968 flicker film T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G for his use of primary colors and its trance-inducing rhythm. By the end of this phase, I had a very weird silent film. I usually create image and sound at the same time or at least conceive of the soundtrack as I am editing. But this was a very different way of working for me. As I was creating the images, I was listening to a lot of experimental jazz from the sixties and seventies or music influenced by that era. I knew the film needed that kind of score. But instead of creating a soundtrack using pirated sound and music as I usually do, I decided to try something new and worked with a composer. Chicago has an incredible jazz scene. I wanted to get to know it better. I heard Ben Lamar Gay perform at the Experimental Sound Studio. His music was exactly what I was hearing in my head when I was editing. I did not know him. I sent him a preview, he liked it and we met a few times to talk about the film, our influences and our distinct methodologies. He would play some demos and I would give him feedback. The whole experience went very smoothly. As always, my long-time collaborator Lou Mallozzi created a fantastic mix of the score. I ended up with exactly what I wanted. It was like magic.

The quoted text raises the question of the source, the copy and the transmission. How do you see the reuse of images of other artists in your own work?

I believe that a work is never finished. When I watch a film, listen to music or read a book, I am always imagining new worlds, reconfiguring the information, creating mash-upsin my head. Knowledge expands. Ideas are infectious. I am never the sole author of my work; I am always in dialog with thousands of other authors, consciously or not. In 2006, I labeled Jean Genet in Chicago a thief’s video. It was of course an allusion to Genet’s book The Thief’s Journal. But all of my work could be labeled a thief’s videos, if you consider ideas as properties (I don’t). Unfortunately, this makes my work illegal or at least non-commercial because of the laws of the world we live in. Burroughs is also a thief. When he writes in Cities of the Red Night/Fever Freaks, “The only thing not prerecorded in a prerecorded universe are the prerecordings themselves”, he is quoting Wittgenstein. He has repeated this sentence on film, in lectures and in other writings. For Burroughs, language is a virus; the word “is an organism with no internal function other than to replicate itself”. In a lecture on creative writing/reading, he said that the concept of originality is now dead, new ideas and characters are no longer necessary and that if a writer uses sets and characters from another writer, the new work should still be judged on its own merit.

If language is a virus, how do you find the original copy, how do you go back to the prerecordings? The detective in Cities of Red Night decided to create another copy of the books instead of searching for the originals. With Fever Freaks, I produced a copy of the books with a Pasolinian difference. I could have shot all new images but that would have missed Burroughs’ point.

Questions Vidéographe, 2017.

Sexuality, William S. Burrough, Pier Paolo Pasolini, literature, cinema