Youhou

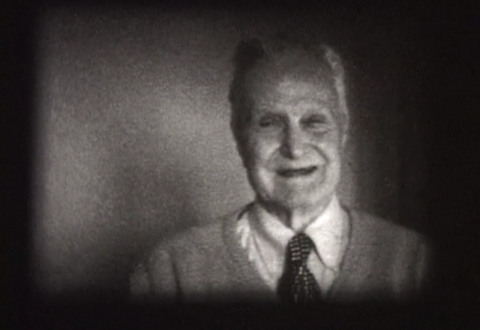

Youhou speaks to the viewer directly but, naturally, the latter cannot respond. Youhou is filmed on a stationary camera, recalling Jochen Gerz’s video Rufen bis zu Erchöpfung (Cry to Exhaustion), 1972, in which we see the artist, far off in the distance, ‘shouting at the top of his voice […] calling without response for 25 minutes’.[1] Both works exemplify the idea of a ‘return to sender’ message and the failure to make contact in the simulacrum of realism that is video’s static sequence shot, returning both the addressor and addressee to their mutual solitude. The failure makes us aware of our impotence as viewers of pre-recorded material and destroys the illusion of being present in the same moment. It highlights the rupture and dissociation that follows the promise of contact through the illusion of connection.

This failed attempt at communication is due to the separation between the simulacrum and the gallery space. The viewer cannot answer this repeated appeal. The simulacrum therefore provokes the keen awareness of loss—the loss of the possibility of action and of answering the other’s call. The heightened awareness of this loss reminds the viewer of the distance that separates him from the image of the other and shatters the illusion of co-presence. It removes the possibility of establishing links and returns the viewer to ‘his absolute isolation and distance’. [2]

[1] Françoise Parfait, Vidéo, un art contemporain, Éditions du Regard, 2001, p. 215.

[2] Stanley Cavell, Projection du monde : réflexions sur l'ontologie du cinéma, by Christian Fournier, Paris, Éditions Belin, 1999, p. 249 (translated from The world viewed: reflections on the ontology of film).

Technical information

Documentation

Mot de l'artiste :

Youhou émet une adresse directe au spectateur, à laquelle celui-ci ne peut évidemment pas répondre. Youhou me montre toute petite, filmée en caméra fixe comme dans cette vidéo de Jochen Gerz, Rufen bis zu Erchöpfung (Criez jusqu’à l’épuisement), 1972, où l’on voit l’artiste, au loin dans le paysage, « s’égosillant […] hélant sans réponse pendant 25 minutes. »[1] Cette œuvre de Jochen Gerz et Youhou sont exemplaires de l’idée d’une fausse adresse, renvoyant destinateur et destinataire à leur solitude réciproque et à l’échec du contact dans le simulacre du médium réaliste qu’est la vidéo en plan-séquence fixe. La fausse adresse invite à vivre et ressentir l’impuissance du différé et le bris de l’illusion de la coprésence. Elle fait survenir la rupture et la dissociation après avoir fait miroiter le contact par effet de liaison.

C’est la séparation entre l’espace du simulacre et l’espace de la galerie qui conditionne l’échec de cette tentative de communication. Le spectateur ne peut répondre à cet appel répété. Ici, le simulacre provoque la conscience vive de la perte. Il s’agit de la perte de la possibilité d’action et de réponse à l’appel d’autrui. Cette conscience avivée de la perte liée au simulacre renvoie le spectateur à la distance qui le sépare de l’image d’autrui et brise l’illusion de coprésence. Elle le dé-saisit de la possibilité d’établir des liens et le renvoie à « son isolement et éloignement absolus »[2], pour reprendre les termes du philosophe Stanley Cavell.

1 Françoise Parfait, Vidéo, un art contemporain, éditions du Regard, 2001, p. 215.

2 Stanley Cavell, Projection du monde : réflexions sur l'ontologie du cinéma, traduit par Christian Fournier, Paris, Éditions Belin, 1999, p. 249.

Body, communication, loneliness, performance